Following numerous reports and articles of human rights violations committed by authorities in the implementation of government-imposed covid-19 restrictions, civil society organizations have mobilized as children and youth’s human rights were largely affected by the restrictions.

»Even in a state of emergency like this, we cannot suspend the fundamental human rights of the people and the children. They must be respected always, but there are many who have raised concerns with that«.

The words come from Rowena Legaspi.

She is the executive director of the organization, Children’s Legal Rights and Development Center (CLRDC) – a human rights organization in the Philippines promoting the rights of vulnerable children and youth.

In February 2020 DIGNITY, CLRDC and the NGO Balay Rehabilitation Center launched a project to protect vulnerable children from torture and ill-treatment in a poor urban settlement in the capital, Manila. The project is called ‘Following the Child: Integrated protection of children along their pathway through the juvenile justice and welfare system in the Philippines’ and is intended to empower children by strengthening their life skills and knowledge of their rights, promote community-based activities aimed at transforming attitudes and behaviors from being punitive to protective, and help ensuring a better monitoring system to document violations and provide support to child victims.

In a country where about 80 percent of all children have experienced some form of violence according to Save the Children(1) such a project is very needed. But the COVID-19 crisis has put the planned activities on hold for the time being.

Instead, Rowena Legaspi and her colleagues, as well as other local children’s organizations, have launched a new monitoring initiative to promote respect for children’s rights under COVID-19, one case at a time. But it is not easy.

The Philippines was amongst the first countries outside China where COVID-19 cases were identified.

Already on March 8, President Duterte declared a public health emergency. A week later, he introduced the so-called ‘enhanced community quarantine’ (ECQ) – a de facto shutdown – in the metropolitan region, Metro Manila. It was later expanded to the largest of the country’s three regions, Luzon, where over half of the Filipino population lives. Many of them in densely populated slum areas.

During the quarantine, a ban on assembly and a curfew between 8 pm and 5 am was introduced. All public transport was suspended, only healthcare professionals and others who carry out vital tasks could move outside, and a maximum of one person per household were allowed to buy necessities like food and water. This is a major challenge – especially for the poorest of the poor. Many have no place to live and are forced to go hungry as they are daily laborers who depend on a daily income. This also applies to the poorest children.

And to make matters worse, police and law enforcement forces have been using heavy-handed methods to ensure compliance, Rowena Legaspi explains:

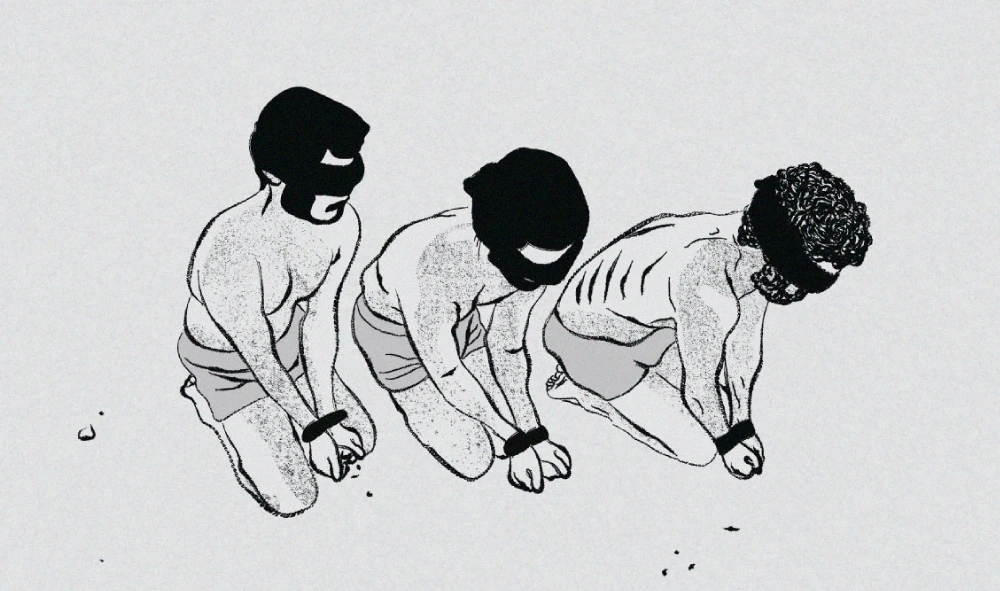

»During this entire quarantine period, many violations have occurred – especially in the implementation of the curfew. CLRDC have received reports and referrals from NGO members of the biggest child rights formation in the Philippines, child rights network (CRN), concerning violations committed against children. The children were reportedly violating curfew hours and were punished inhumanely with punishment methods ranging from arbitrary arrest to torture, inhuman treatment and other related violations committed by the authorities«.

As an example, she mentions a case referred to CLRDC by a local NGO based in Manila.

»It involved 7 people – 3 of them minors – who had allegedly violated the curfew hours according to authorities. Based on the incident report we received, the victims had been taken into the local police station and shamed, their heads were shaved, and some were beaten. They were forced to stay in a custodial facility for the next 24 hours and in the morning, they were exhibited to the public as an example. The authorities used them to show how they could be treated if the curfew was violated«.

This is just one example of the reported violations of children’s rights that have transpired during the COVID-19 crisis. To try and address this, CLRDC and several other NGOs have started a monitoring network and initiative to document as much as possible.

From her living room, Rowena Legaspi and her colleagues monitor social media and news platforms as well as gather information from local staff who may know of cases of violations against children.

If a documented case is confirmed, the CLRDC will then contact the local authorities and, if they do not respond, they will reach out to the Child Rights Center at the Human Rights Commission of the Philippines to put pressure on the system, get the minors released or open a case.

According to Rowena Legaspi, this has been effective in several cases.

»In one case, we were told through networks and later in the news that the police had charged about 19 vendors – including three minors – with violation of the enhanced community quarantine because they were on the street selling vegetables. In that case, the Human Rights Commission wrote to the local mayor and he later told that all 19 were released again – including the three minors«.

Further, the Department of Interior Local Government and the Council for the Welfare of Children have published a joint memo in the beginning of April, which provides for the protection of children abused during covid-19 pandemic.

These are positive developments, but it is a slow process and it is frustrating, Rowena explains.

From March 16 to April 30 LRDC has documented 58 cases, but they are only the tip of the iceberg. Rowena fears that many more will come – especially cases of online sexual exploitation.

»I fear several cases of human rights violations. Not only cases of violence against children, but also cases of discrimination against LGTB persons, cases of incest and domestic violence (…) I further fear an increase in child sexual abuse cases. In poor countries like the Philippines, there are some people who want to take advantage of the situation for poor families. We have reports from past that show that some people involved in child trafficking or child pornography use social media to surge for victims. And some parents or other adults use the children for prostitution or exploitation online. We cannot avoid this in times when people need to eat«.

Rowena Legaspi therefore hopes that the quarantine will end soon. From the 16th of May society will slowly open, but only a few more people will be allowed to work and travel. She does not suspect any changes for the vulnerable youth and children and wants authorities to ensure necessities for the poorest people, who have no other options in terms of food and shelter.

»We call on the government to ensure that children – and especially the marginalized children – will have access to basic services and like food, water and shelter. And that their rights are not violated when arrested because of the curfew or quarantine. The local government units and every barangay should be aware of this to ensure children’s rights are protected during this time of pandemic. «

[1] According to a national study on violence against children (2016), 80% of Filipino children have experienced some form of violence in their lifetime. This includes physical and psychological violence, sexual violence, bullying, exploitation, and violence in the internet.’ à see https://www.savethechildren.org.ph/our-work/program/childs-rights-and-protection/